Traffic growth in Europe over the past 6 years has been so strong as to question whether ours is a mature market. İGA’s new airport in Istanbul is emblematic of grand ambitions for future growth. Aircraft manufacturers order books are bulging for the years ahead. Between 2000 and 2020, China will have built 69 new airports – many of which will connect to European destinations. Joining the dots, it’s clear that more airport capacity will be needed. So, how can we live the contradiction of a Europe in which everyone wants to travel, but airlines want ever cheaper access to airports? By Michael Stanton-Geddes, Head of Economics & Competition, ACI EUROPE.

ACI’s most recent long-term traffic forecasts expects that Europe’s airports will welcome 4.4 billion passengers in the year 2040 – a staggering number. That is double the traffic volume seen in 2017, a year during which many travellers already felt that airports, aircraft and skies were saturated. For the industry to meet this forecast, coordinated efforts are required to ensure that adequate equipment and infrastructure is built and financed.

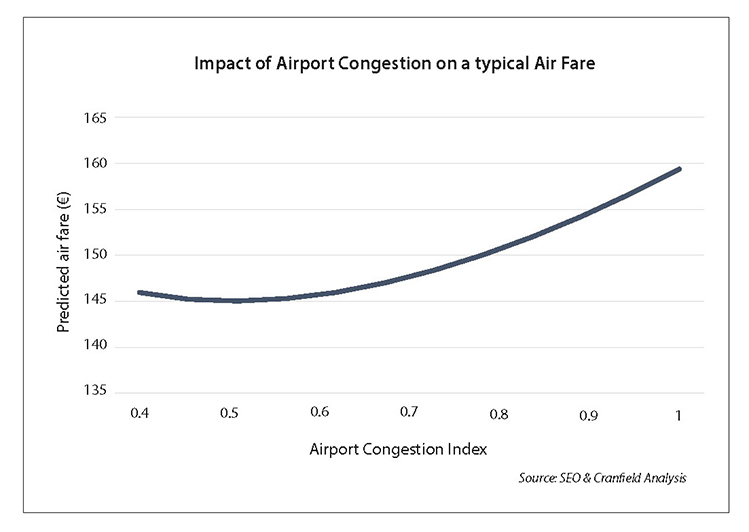

SEO Amsterdam Economics & Cranfield University’s analysis has provided key insights into the impact of airport congestion on air fares.

While the European forecast may seem unattainable, the air transport industry has already delivered an increase of 31% in passenger numbers over the past 5 years; 2012-2017. Competition between airports is leading to new connections, and European airport connectivity has expanded by 25%. Airport passenger service quality improves annually. And during that same time period, for 5 consecutive years, headline airport charges levels in Europe actually decreased year on year, declining by -1.25% in real terms in 2018. More than 50 airports decreased or held constant their headline levels of aircraft charges.

There is more. That decrease in the level of published charges does not include the effect of incentives. Incentive payments and rebates further reduce the costs of infrastructure for airlines. According to ACI EUROPE’s survey, 98% of airports now offer an incentive scheme to airlines, an increase over past years. Airport operators offer incentives to any airline meeting criteria, with the aim to increase capacity utilisation, develop new routes or promote specific types of traffic. Incentives further reduce the actual cost of using the airport for airlines, so airports are able to use the incentives to compete for new aircraft and new routes.

Here lies the paradox. In this period of intensifying airport competition, passenger traffic growth, investment and airport efficiency, the topic of economic regulation has been raised again. In the European Union, the Airport Charges Directive entered into force only in 2011. Nonetheless, IATA and Airlines for Europe (A4E) have lobbied for the European Commission to revise the Airport Charges Directive, asking for “effective regulation”. Responding to stakeholder concerns, in December 2015, the European Commission’s Aviation Strategy committed to reviewing the Airport Charges Directive, and the European Commission followed with plans in 2017 to assess potential future policies.

An explanation for this paradox can be found in the principle of loss aversion as understood in behavioural economics. Building infrastructure to meet the demand forecast for 2040 will require infrastructure that can handle double today’s traffic. This will have a cost: here in Europe where users pay for the infrastructure, not governments or taxpayers. Consider the ongoing hand-wringing for public finance to address aging infrastructure in the USA.

Loss aversion is frequently summarised as “the loss looms larger than the gain”. Airlines care more about their supplier costs next quarter than about ensuring there is sufficient capacity to meet demand in 5 years and beyond. So, airlines may prefer to avoid small increases in landing charges, rather than realise the gain of an expanded airport offering more capacity and higher quality service. Because airlines see the loss, they are blind to the gains from quality improvements. This reflects the challenges of airlines’ short term view, versus airports’ long term view.

The gains of investment are apparent as soon as the passenger steps foot in an airport that focuses on delivering quality and ensuring comfort. However, individual airlines will continue to seek to lower their supplier costs (avoid the loss) rather than focus on the gains. As suppliers, airports will continue to deliver optimal service to their airline customers and passengers while actively competing for new customers.

Airport operators offer incentives to any airline meeting criteria, with the aim to increase capacity utilisation, develop new routes or promote specific types of traffic. Incentives further reduce the actual cost of using the airport for airlines, so airports are able to use the incentives to compete for new aircraft and new routes.

At this point, it is worth recalling that airport charges are a small part of an airline’s costs. Most passengers travel with airlines for whom airport charges represent 6% or less of their cost base. So an increase in airport charges is counted in cents per passenger, but because of current capacity constraints, airlines will always exert their pricing power irrespective of the level of airport charges.

Distracted by a debate on economic regulation and market power, the real risk is that we lose sight of the travellers needs for airports that offer capacity and comfort. The need for additional airport capacity in Europe to meet projected future demand is recognised by all – airports, passengers, national ministries of transport, EU institutions, even airlines. However, regulators need to remain aware of these risks and not heighten the risk assessment of investors through unnecessary efforts to change the regulatory framework.