Airport competition in Europe is an established fact of life. The impact of airport competition can readily be seen at route development conferences, such as the World Route Development Forum, where airports clamour and queue for the opportunity to display their wares to airlines. But if you haven’t been to one of these events, simply skim through the magazine you are currently reading. You’ll find examples of airports focused on efficiency, on customer service, on commercial efforts and partnership with other industry stakeholders. You’ll see advertisements promoting airport brands, and soliciting new business. These activities are not those of bloated monopolists, sitting back while revenues simply roll in. Rather these are the actions of lean and hungry companies, fighting and innovating to maintain their slice of the market.

Dr Harry Bush: “Most European airports are now subject to competitive discipline from one or more sources – this should usually be sufficient to protect passengers and airlines.”

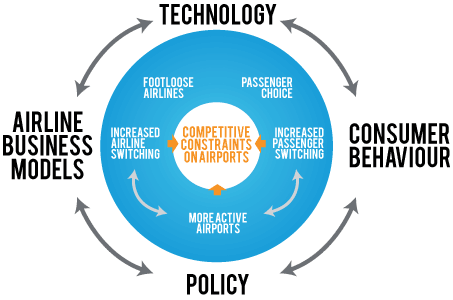

The causes of this revolution stretch back to the 1990s. The liberalisation of the European airline market, and subsequently of bilateral agreements with many third party countries, changed everything. The move opened up airlines to full competition, and airports soon began to feel the knock-on impact. In this emerging competitive landscape, new airline business models came to expect relentless cost discipline from their suppliers, including airports. Structural changes accelerated these trends. Long haul routes are no longer the preserve of large hub airports, with new aircraft technology opening the market to secondary airports. Passengers became more discerning, and with a wider choice of airports than ever before, embraced information technology to ensure that they were making the right choices.

In parallel, airports embraced a new commercial approach, employing techniques such as branding and active marketing to airlines. Alongside this, new corporatised structures were adopted to best leverage airports’ commercial potential. All this further contributed to the competitive dynamic.

But while competitive forces have been busy reshaping the industry around us, the reality does not always seem to have filtered up to public decision makers. The evidence is all around us, but the dots have not yet being drawn together, obscuring the bigger picture. This matters a great deal, because these regulators are imposing – to varying degrees – restraints on airport commercial freedom which incur significant economic costs. Alongside the immediate significant direct costs of regulation, short-term prices may be distorted. In the medium-term regulation can incentivise investment in the wrong infrastructure. In the long-term, regulation can undermine the development of the best new technologies and business strategies.

A new independent Study by Copenhagen Economics, Airport Competition in Europe may help point a way forward from this sorry quagmire. Pushing rhetoric to one side, the Study takes a cold clinical look at the issue of airport competition, using hard data, economic and legal definitions of competition, and a range of quantitative analytical techniques. The team behind the Study had no shortage of experience to draw upon either – it was steered by Dr Harry Bush, former Group Director of Economic Regulation at the UK Civil Aviation Authority, who oversaw the economic regulation of Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted, among others.

The findings of the Study are unambiguous. There are a variety of competitive pressures facing European airports. As Dr. Bush notes “Most European airports are now subject to competitive discipline from one or more sources – this should usually be sufficient to protect passengers and airlines.”

Airlines have a wide selection of airports to choose from, and they are making full use of their freedom. Route ‘churn’ is substantial, with route openings accounting for 20% of the market, and route closing amounting to 15% of all routes in a year, as airlines chop and change routes to maximise margins.

Airlines are also enjoying increased buyer power, which in many cases, more than counters any market power which airports might otherwise have enjoyed. Across all airports with more than one million passengers, 84% cater for an airline which comprises more than 40% of an airport’s capacity – that equates to an airline customer with a lot of muscle at the negotiating table.

Passengers too can pick and choose their airport of preference. Close to two thirds of Europeans are within a 2 hour drive of 2 or more airports. Route overlap is high, too. An analysis of a sample of airports showed that over 50% of destinations at the largest airport are also served by one or more airports around it. And this freedom of choice is not limited to origin-destination passengers. 62% of transfer passengers have one or more realistic alternative hubs to transfer through.

This freedom of choice matters a great deal. In fact, it is the essence of competition.

The impact of airport competition can readily be seen at route development conferences, such as the World Route Development Forum, where airports clamour and queue for the opportunity to display their wares to airlines. © UBM Aviation Routes Ltd

If a dissatisfied airline or passenger can go elsewhere, then the airport knows that it must provide the right service at the right price to maintain that customer. This is particularly so for airports, which face a ‘double blow’ for each lost unit of traffic. If an airline decides to cut a route, an airport’s costs, being predominantly fixed, do not change by much, if at all. However, revenues drop dramatically – not only the aeronautical charges, but also the commercial revenues that passengers would have raised, had the route remained. The resulting gap between costs and revenues can be a very immediate and painful hole in an airport’s balance sheet.

So airports have had to be quick and energetic in their responses to competitive pressures.

Supplying a desirable product is key to these efforts. To this end improving service quality is a key objective of many airports. While there are multiple individual examples of this, it is evident at an industry level also. 38 European airports took part in the Airport Service Quality (ASQ) programme between 2006 and 2011. In that time the average score for these airports increased by 8%.

And airlines and passengers are not paying for these improvements. Significant price pressures have seen the average European airports become cheaper relative to its international peers. This trend was boosted by the financial crisis of recent years. Responding to weakened demand in a competitive manner, almost 70% of European airports either lowered or kept their charges stable in 2009.

Having created the right product at the right price, airports then have to embark on intensive marketing campaigns. 96% of European airports actively market their airports to airlines – it is now an integral part of the business. Indeed, European airports consistently outperform their global counterparts, when it comes to participation on a range of different route promotion activities. These efforts are being augmented by route incentive schemes. Airports know that airlines expect them share the risk, if they want to share the benefits from new routes.

A new independent Study by Copenhagen Economics, Airport Competition in Europe takes a cold clinical look at the issue of airport competition, using hard data, economic and legal definitions of competition, and a range of quantitative analytical techniques.

Taken as a whole, the evidence within the Study is indisputable. European airports have risen to the challenge of airport competition – it is now the turn of European regulators to do the very same.

Regulation cannot remain static while the regulated industry transforms radically. Orthodox economic theory and experience points a clear path for decision makers – where there is no market power, do not regulate. Where there are vestiges of market power, regulate commensurately. The variety of competitive pressures which airports are facing suggests that even when intervention is necessary, regulation should be less, but more effective, to ensure that competition is allowed to fully develop. Reflecting on the challenges facing regulators, Dr. Bush said “Regulators now need to ensure that the framework is fit for purpose – to do otherwise risks obstructing the development of the very competitive forces that have done so much for European passengers and airlines to date”.

Airline liberalisation by European regulators in the 1990s gave birth to a wind of change. This wind has blown across airlines and swept through airports, bringing irreversible change. It has now come full circle, returning to European regulators, demanding that they recognise the changes that it has wrought. The Airport Competition Study should help them do just that.

‘Airport Competition in Europe’ is available in the Policy Library section of the ACI EUROPE website – www.aci-europe.org. All figures referenced in this article are sourced from the Study.

Study Methodology

‘Airport Competition in Europe’ is an independent study by Copenhagen Economics, with former UK CAA Group Director of Economic Regulation Dr. Harry Bush as steering director. The study takes an evidence-based approach. As there is no single method or indicator to assess the degree of competition between airports, a range of different analysis have been employed. These combine pan-European data and models with surveys, case studies and other available evidence.

Data ranges between 2002 and 2011 – the longest time span for which comparable data and models are available. While this does not fully capture the changes that have taken place since the liberalisation of European aviation in the mid-1990s, it is enough to detect clear trends.